Employees climbed into the driver’s seat and tipped the balance of work. Here’s what to expect in 2023.

2022 was a lot of things, but when it came to the workplace, it was a year of tipping the balance of power. It effectively reshuffled the cards for what the future of work would look like.

After two long years of stops and starts, employers sought normalcy, reshuffling real estate and rethinking the purpose of the office. They hedged against raging inflation, supply-chain challenges and a recession that has still yet to transpire. The economy itself was imbalanced: high inflation and supply-chain shortages countered severe labor shortages and strong financials among business, government and individual consumers.

Employees, meanwhile, climbed firmly in the driver’s seat this year, due to a labor shortage, the Great Resignation, quiet-quitting and unprecedented burnout rates. At least 4 million people quit their job each month in 2022, following the record 48 million people who did in 2021.

Much of that job market power comes down to numbers—or, really, a lack of numbers. Baby Boomers have been retiring and leaving the workforce at expedited rates since COVID-19, and immigration has slowed to a crawl. Demand for services and goods hasn’t slowed, but the people needed to deliver them has declined.

Nick Fewings, Unsplash

Employees boosted expectations from work

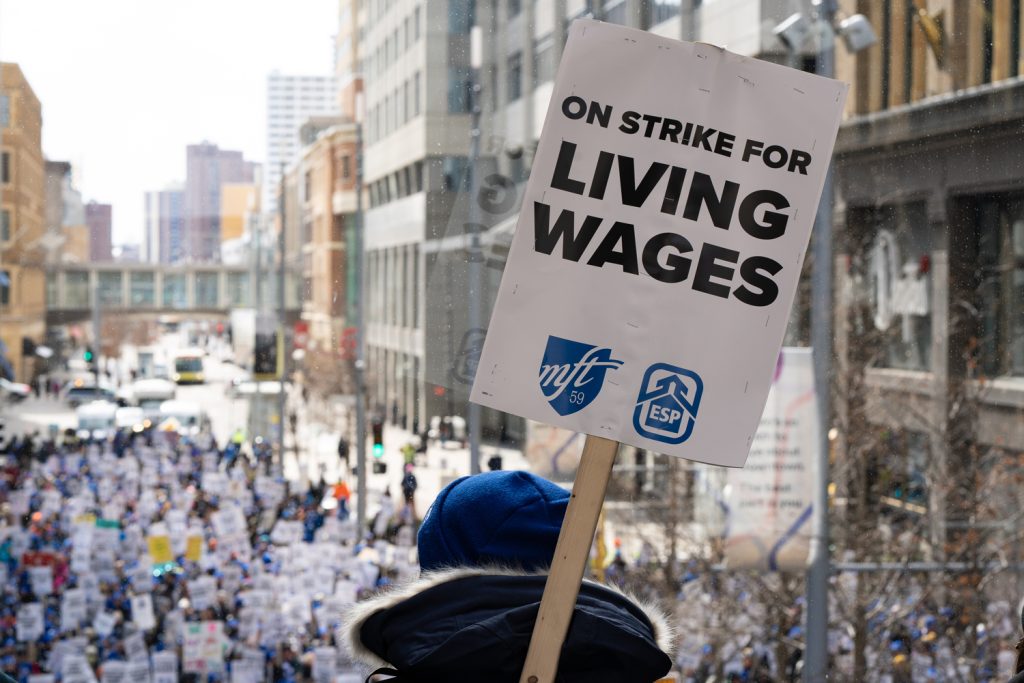

Employees sought balance at work. They demanded workplaces with serious commitments to diversity, equity, inclusion, environmental sustainability, flexibility, and self-development and mentorship. They requested more support around mental health and overall wellness. As a result, human resource officials began to think like marketers— carefully analyzing what work is like for their employees to make it better. That “employee experience” included everything from in-office interactions and people’s stress levels, to compensation and whether people are getting promoted. Younger workers, especially women, weren’t afraid to ask for what they wanted—or walk out the door.

Employees—not employers—also called the shots when it came to the return to the office. Leaders began to rethink whether a corporate headquarters was necessary and what exactly the office meant in the age of hybrid work, and more decided it would become primarily a place for professional development, collaboration, connection, mentorship and culture building. Employee needs would alter what the office would look like going forward, they would dictate real estate decisions and they would determine flex schedules about who would walk through the office doors, when and how often.

Chad Davis, Flickr

But people were still exhausted in 2022

The same labor shortage that put employees in charge, however, had a big downside: exhaustion. People are simply tired. They’re working longer hours with fewer people to share the load, and with less enthusiasm. Workplace burnout, while lessening some from the year prior, continued throughout 2022 as people felt new pressures around the return to office and in-person meetings. Layoffs in the tech sector and talk of recession only added to that stress.

Christian Erfurt, Unsplash

“Burnout is not going away,” says Jennifer Moss, a journalist and author of the book The Burnout Epidemic. In some industries, such as education, healthcare and retail, she says, it’s getting worse with long hours, illness, depression, violence and fewer people to do the work.

In December, 89% of workers, 91% of HR leaders, and 82% of the C-suite said they were experiencing work-related stress, according to a new survey of 3,400 people by Workforce Institute at UKG and Workplace Intelligence. At least two-thirds of workers and HR executives and half of top executives said that work stress negatively impacted their wellbeing and health.

“Well-being is going to be the No. 1 trend next year,” says Dan Schawbel, managing partner of HR research and advisory firm Workplace Intelligence and author of Back to Human: How Great Leaders Create Connection in the Age of Isolation.

A shifting balance

Employee power appeared to temper a bit at the close of the year. Countless tech companies began rounds of layoffs and some companies, including Elon Musk’s Twitter, demanded people come back to the office full-time and began to move away from flexible work.

The threat of a recession impacted how people viewed their jobs: 61% of workers said they would be willing to take a pay cut to avoid being laid off if there is a recession and three-quarters of Americans said they planned to stay put in their current job due to the current economic environment, according to surveys by staffing firm Insight Global.

The economy also remains confusing. Either job growth must slow sharply, GDP must regain its footing or some combination of both, says Mark Zandi, Moody’s chief economist. “Boomy employment gains and falling GDP are incongruous and will not last long in tandem,” he says.

Yet economists do not necessarily see the labor shortage ending any time soon without an influx of immigration. The U.S. still has nearly 11 million unfilled jobs, according to the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and the working-age population has plateaued. Employers know how hard it’s been to get workers, so they may be less inclined to lay off workers.

But tensions are rising. As many as 85% of employees worldwide could be “quiet quitting,” or doing the bare minimal tasks of a job, enough to not get fired. Productivity was down 1.4 % in the third quarter of 2022, but people were working 3.4% more hours, according to the November Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“The reality is the executives and managers who I speak to regularly are all frustrated with declining productivity,” says Kane Carpenter, managing director at Daggerfinn, a Detroit employer branding and growth strategies consultancy.

Employees and managers often disagree on how exactly to improve productivity, according to research by Microsoft and data from WFH Research. Many managers believe productivity boils down to being in the office where others can see you work, while most employees say remote work gives them more control over how to deliver their goals, says Ian Cook, vice president of research at Visier, a Canadian workforce analytics firm.

While the knee-jerk reaction to boost productivity might be to call everyone back to the office full-time, that could easily become a “clash of the titans,” without flexibility, says Laura Mills, Forage, head of early career insights at Forage, an ed-tech startup.

Trust will be crucial going forward, Cook says. When employees don’t feel trusted, they withdraw discretionary work. They may also quit, especially when jobs are available. When managers don’t feel like they can trust employees, it elevates stress and hurts relationships and breeds miscommunication, missed deadlines and missed outcomes. “This is a lose-lose result,” says Cook.

Customization and flexibility will drive 2023

Carpenter believes that going forward, the office will continue to be the place to connect and collaborate rather than simply a place to do heads-down work every day. Hybrid technologies that can bridge the remote and in-office experience will continue to flourish. And smart companies will increasingly rely on data, versus anecdotal evidence, to build hybrid work strategies, and they will adjust schedules and workloads based on an individual, her job, and where she lives. “A one-size-fits-all,” he says, “is no longer relevant.”

Balance is possible in 2023—in terms of workload, flexibility, wellness and employee-employer power. And those leaders that embrace it will be far more likely to attract and retain the best employees—and ultimately boost productivity, happiness and growth.